3rd edition as of August 2023

Module Overview

In this module, we will focus on the educational experiences of males and females. We will look at how experiences differ in the preschool and school ages. We will also discover how school performance in various subjects differs between genders. We will also consider the concept of academic motivation, factors that contribute to academic motivation, and gender differences in this motivation.

Module Outline

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe preschool-age experiences and how gender impacts these experiences.

- Describe varying abilities and experiences in school-aged children.

- Outline the factors that differentially impact boys’ and girls’ performance and motivation at school.

10.1. Preschool

Section Learning Objectives

- Define self-competence and self-esteem clarify how they impact school experiences and differ between boys and girls.

- Clarify the role play has in preschooler’s development and how play varies between genders.

10.1.1. Self-Competence

A child’s ability to self-regulate, or manage their behavior following experiences of stress, excitement, or arousal, can lead to better social competence. Social competence is the ability to interpret and evaluate social situations and make decisions about acceptable ways to respond. High social competence leads to higher self-esteem and self-concept, the ability to cope with correction and failure. A high self-concept leads to higher social school readiness, or higher cooperation with peers, positive views about school, fostered ability to listen and focus (Joy, 2016).

10.1.1.1. Self-Esteem. Preschoolers tend to have very high self-esteem (Harter, 2006). This is likely because preschoolers struggle to truly differentiate the level of difficulty in a task and overestimate their own abilities which leads them to trying challenging tasks more often and exposing themselves to learning a variety of skills. This fosters motivation and learning in preschoolers. Overall, boys and girls tend to have similar self-esteem (Marsh & Ayotte, 2003; Young & Mroczek, 2003; Cole et al., 2001); however, people on average assume that boys have higher self-esteem, and it may be that girls internalize this assumption. Thus, some studies show that girls have lower self-esteem (Hagbor, 1993).

Parenting styles and teachers can certainly impact self-esteem in young children. Parents that practice warm, but firm parenting (authoritative parenting), have children with higher self-esteem. Parents that are overly correcting or controlling deny children the ability to develop self-esteem fully, and these children have lower self-esteem ratings (Donellan et al., 2005; Kernis, 2002).

The model-observer similarity hypothesis posits that when learners perceive themselves to be similar to the model, or the teacher, then they will show greater self-efficacy. However, there is mixed support for this, and which is largely explained by what is being learned. Overall, when a model is the same sex as us, it does not change how much we learn, but it does impact our behavior. This is because we internalize the behavior as appropriate if a same-sex model does it, and the environment accepts it. Task appropriateness (male versus female tasks), is learned best by same-sex models. Students perceived same-gender models as more similar to them than other-gender models. Same-sex models may also increase perceived confidence, but do not necessarily improve performance, increase confidence, or increase self-efficacy (Hoogerheid, van Wermeskerken, Van Nassau, & Van Gog, 2018).

As children get older, self-competence declines. The rate at which it declines depends on the subject area. For example, self-competence increases for sports, but declines for language arts. Specifically, research indicates that males tend to have more perceived self-competence in sports and math, and females have more self-competence in language arts (Jacobs, Lanza, Osgood, Eccles, & Wigfield, 2002).

10.1.2. The Role of Play in the Development of Gender Roles

As you might expect, preschool children engage in play as a primary activity in their preschool setting. This is developmentally appropriate for them, and they gain extensive knowledge about their world and environment through play. Play provides children and their peers an opportunity to test out different roles and ideas as well as to provide feedback as to what works and what is acceptable and preferred by peers. Sex-role socialization theory states that society shepherds children into different roles to fulfill differentiated roles in adult life, paid labor outside the home for men, and unpaid housework labor and child rearing for women. The theory proposes two opposite categories of sex – male and female (Martin & Beese, 2017). Thus, play is ether masculine or feminine and either aligns with the male-sex role or female-sex role. Playing with baby dolls aligns with the female-sex role of nurturing and child rearing, whereas pretending to build with toy tools aligns with the male-sex role of paid labor.

Interestingly, before the age of 2, it is difficult for children to distinguish between boys and girls. Children show a preference for sex-typed toys that match their sex, for example, dolls or cars, between 12 and 18 months (Serbin et al., 2001). However, at this age, children are not able to match the sex-typed toys with male or female faces and voices, indicating they have not yet been socialized into thinking of toys as either “female” or “male.” Even less influenced by human socialization are nonhuman primates, who also show preferences for sex-typed toys. Female monkeys preferred playing with soft toys and dolls, and male monkeys preferred playing with balls and toys with wheels (Alexander & Hines, 2002). By age 5, children will not only prefer to play with their own gender, but they will also likely reject or show a bias against the other gender (Martin & Beese, 2017; Hill & Portrie-Bethke, 2017; Hill & Haley, 2017).

It has been suggested that in order to reduce the effects of socialization on gender and create gender-equal environments, teachers can provide models and examples of non-sexist behavior. Moreover, they can encourage gender equality by choosing gender neutral language, for example, firefighter rather than fireman. Teachers could also provide encouraging environments for children who deviate from typical gendered play norms, such as boys playing with dolls and use visual materials that are gender neutral or show both genders performing a task. Although these may be recommended, they may also be largely ineffective, according to research (Martin & Beese, 2017).

Another theory about gender-role development in the context of preschool and play is the Feminist Post-Structural theory. This theory suggests that children not only model gender-normed behavior, they construct their own gender. This theory suggests that gender is not specific to distinct categories; rather, female is defined in relation to male and vice versa. Thus, masculine and feminine characteristics are actually interdependent and exist within a continuum. This theory proposes that, because of this, there is an emotional investment in gender roles and encouraging nonsexist behavior is not appropriate. It is suggested that doing this requires an individual to give up something they perceive as desired and pleasurable. For example, if a girl is encouraged to play with trucks instead of dolls, but they find pleasure in playing with dolls, she has been asked to give up a toy she truly likes and enjoys (Martin & Beese, 2017).

Twenty-five percent of girls reported feeling teased by boys, usually in ways such as boys pushing them too hard on a swing, hitting them, etc. This could lead to a preference in some girls to play with other girls, rather than boys. As such, encouraging nonsexist play and forced gender-mixed play may not be the best option – at least from a feminist post-structural theory standpoint (Martin & Beese, 2017).

10.2. School

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe math abilities in girls.

- Describe academic achievement in boys.

- Describe the various components of school culture that contribute to boys’ and girls’ experiences at school.

- Clarify what is defined as “masculine” and the consequences that occur when males do and do not align with the “cool” masculinity traits that are scripted for them.

- Define gender tracking and clarify how it occurs in the school-setting.

10.2.1. Math Ability in Girls

As you know by now from our discussion in the cognitive chapter, there are minimal differences in actual cognitive capacities between genders, and math is no exception. However, girls are often perceived to have lower math abilities by adults (e.g., parents and teachers; Tomasetto, Alparone, & Cadinu, 2011; Beilock, Gunderson, Ramirez, & Levine, 2010), peers, and themselves (Correll, 2001). As we discussed with stereotype threat and self-fulfilling prophecies, this perception may lend itself to girls performing lower in math. It is not that girls have genuinely lower math abilities, rather, social and environmental factors impact girls’ math performance, leading to lower math performance.

Despite having equivalent math abilities, girls tend to take fewer math and STEM-related courses in grade school years. Because of this, they may be less prepared to pursue STEM-related majors in higher education years, and thus, pursue careers in STEM fields at a lower rate than males. There have been some efforts to combat this, and those efforts may be working. Rates of females pursuing STEM-related fields increased. In fact, there appears to be equivalent numbers of males and females seeking STEM-related courses in grade school and even in college. However, this does not necessarily carry into careers, as men are more likely to earn a degree in a STEM-major and securing STEM-related careers (Martin & Beese, 2017).

10.2.2. Boy’s Achievement

Although boys get more attention from their teachers, they tend to underachieve compared to girls, and they are falling further and further behind in school performance (Kafer, 2007). Girls are more engaged in school on average, perform higher in academics, are more likely to go to college, and are more likely to complete their college degree, compared to boys. Boys, on average, experience more academic struggles and are referred for behavioral problems more often than girls. In fact, about 60% of special education services are for boys. Boys are also more susceptible to using substances, getting either suspended or expelled, dropping out, going to jail, and dying by suicide or homicide. While there are some proposed explanations for this, more research is needed (Kafer, 2007).

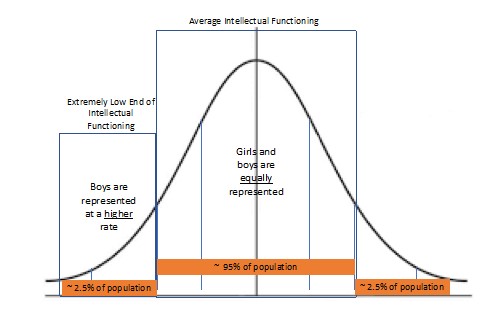

Figure 10.1. Extreme Scores in Males

One proposed explanation is a difference in intelligence, however, boys and girls equally fall within the “Average” area of intellectual functioning, meaning boys and girls are equally represented in the middle of the bell curve (see Figure 10.1).When we examine the extreme lower end of the curve (left of middle; see Figure 10.1), boys may be represented at a higher rate than girls, meaning boys are more likely to have lower cognitive functioning abilities than girls, when looking at only low intellectual abilities (Kafer, 2007).

Another explanation is that schools may not focus enough on boys’ literacy and reading skills. Although there is a literacy gap noted in public schooling, this gap is not found in homeschooled children (Kafer, 2007). Neall (2002) recommends that, within school settings, boys’ self-esteem can be raised by teachers praising achievements and reminding them of their success, encouraging their desire for competition and high activity by fostering their involvement in competitive sports and allowing them to move more when learning, perhaps considering single-sex classrooms, and increasing male teachers (see the model-observer similarity hypothesis in Section 10.1.1.1; Skelton, 2006). However, as previously mentioned, boys already receive more attention than girls in school.

10.2.3. School Culture

The culture created at school and in a classroom is incredibly important for youth outcomes. Much of culture comes from social norms and expectations. For example, girls are expected to be quiet and prosocial. They receive a great deal of praise for these qualities and a strong focus is placed on their appearance. If girls stray from these expectations, they may receive negative evaluations. For example, girls are not expected to be assertive, so when they exhibit assertiveness, they are often labeled as disruptive (Martin & Beeese, 2017).

What about when peers do not conform to gender norms or identify as non-heterosexual? What is the school culture like for them? When students do not conform to gender norms or identify as heterosexual, despite increasing acceptance and tolerance, there still remains a high level of hostility. These students often experience sexual harassment and discrimination. These experiences at school, due to the culture that persists, may lead to these students avoiding school and under-engaging, leading to poorer outcomes academically. Increased emotional distress has also been observed. (Martin & Beeese, 2017).

10.2.4. “Cool” Masculinity

Masculinity, particularly as an adolescent, is highly valued in our society. To be perceived as masculine, boys must avoid looking weak, limit their emotional expressions, be competitive, and exert power and control. Anger and aggression are not only acceptable, they are often encouraged, when in conflict. We socialize this from a young age, expressing direct and indirect messages to young boys that crying and backing down are signs of weakness. In fact, when boys do not appear masculine and adhere to these expectations, they are often ridiculed by peers. While males may reinforce masculine traits in other males, when a female reinforces a male’s engagement in masculine behavior, it is more powerful and salient (Smith, 2017). If a boy is perceived as too feminine, they are heavily ridiculed. Despite females being somewhat encouraged when they break gender norms and display interest in some stereotypically masculine areas, sports for example, boys may not receive social encouragement when they deviate from traditional masculine roles and characteristics. In fact, they are often shamed.

Interestingly, when males are encouraged to restrict their emotions and appear tough, aggression toward themselves and others may also be encouraged (Feder, Levant, & Dean 2007). Aggression is often encouraged in males. Soldiers and first responders, who are usually men, are celebrated for restricting emotions to appear brave and courageous. Aggression in males is also modeled on television. Miedzian (2002) defines this focus of aggression in males the masculine mystique. Boys with higher socioeconomic status (SES) and more resources may find appropriate ways to manage negative emotions, whereas boys with lower SES may struggle to find similar coping methods, resulting in more aggression and criminal behavior.

10.2.5. Gender Tracking

Gender tracking is when students are channeled into different areas of focus/paths solely based on gender. Although this can happen overtly, it may more commonly happen covertly. How children are gender tracked may vary based on age. For example, we begin gender tracking children as soon as we know the sex of a baby – choosing toys, clothes, names, and décor that are specific to their gender. In elementary school, and teachers continue to track girls and boys into playing with gender-typical toys. These are more overt channels. Cover tracking could include teachers calling on boys and attending to them more often than girls, leading girls to raise their hands less frequently. Moreover, boys tend to be identified as requiring special education services more, thus tracking them into an alternative school option more frequently (Jones, 2017).

Tracking in secondary education may be two-fold. First, lower achieving students may be tracked into vocational learning. Boys are often tracked into stereotypically masculine trades (mechanical and masonry tasks), whereas girls are tracked into stereotypically feminine trades (e.g., food trades, child care, and cosmetology). One concern is that feminine trades often have lower incoming potential (Jones, 2017).

High achieving youth are also tracked. Males tend to be tracked into STEM-related classes, whereas higher achieving females tend to be tracked into humanities, social sciences, etc. The only areas that seem immune to gender tracking is history and biology, with both males and females equally represented (Jones, 2017).

10.3. School Performance

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain how teachers impact the academic performance of boys and girls.

- Outline the benefits and drawbacks of single-sex schooling.

- Clarify the factors that contribute to academic motivation and how gender may differentially impact motivation.

10.3.1. Teachers

Teachers play an important role in a child’s educational experiences. While teachers often have good intentions, and verbalize a desire to help each of their students equally, teachers have biases that they are sometimes unaware of that impact educational experiences of students. This bias occurs when teachers form expectations for how a student will perform based on factors unrelated to their prior academic performance. Those factors may include the child’s gender, racial or ethnic identity, or their social/financial status. Sometimes these biases are unconscious, and teachers are unaware of them. The beliefs people have that they are not aware of are referred to as implicit beliefs; (Casad & Bryant, 2017).

Robert Rosenthal, one of the first researchers to examine teacher bias, described the “Pygmalion effect”, or when teacher’s expectancies were shown to impact IQ scores (keep in mind, IQ is not a construct which should be impacted in this way). Moreover, the younger a student was, the more likely their score was to be impacted (Casad & Bryant, 2017; Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968). Ultimately, if a teacher expects a student to underperform and treats them accordingly, the student will be less likely to persevere and try harder in a challenge, which will result in a lower performance on the task (Casad & Bryant, 2017). In this way, the expectations of teachers can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies in students and may contribute to achievement gaps (Robisnon-Cimpian et al., 2014). How teachers communicate to boys and girls, particularly if they foster expectations that boys will be better in math and girls better in language, may contribute to self-fulfilling prophecies that are reflected in gender gaps in math and language (Robinson-Cimpian, et al., 2014).

10.3.2. Single-Sex Schooling

Single-gender or single-sex schooling is a controversial topic. While some are proponents of this option, others strongly discourage it. To understand the controversy, let’s consider each side and the reasons for their positions. Then we will discuss what the research supports.

10.3.2.1. In favor of single-sex schooling. Proponents indicate that boys and girls learn differently; that there are differences in how their brains are developed and in their abilities. They argue single-sex schooling would account for this and tailor education specific to a child’s potential learning/cognitive strengths and weakness based on their sex. Proponents of single-sex schooling argue that the nature of single-sex classes would eliminate gender biases and discrimination, particularly for girls (Halpern et al., 2011).

10.3.2.2. Against single-sex schooling. Recall that are very little differences, cognitively speaking, between girls and boys. Thus, those against single-sex schooling state that the argument used by proponents of single-sex schooling is founded on pseudoscience and does not have any real basis. They also say that these settings increase gender division, segregation, and stereotypes due to the divide they present. Research supports this argument (Hilliard & Liben, 2010; Bigler & Liben, 2006; Martin & Halveron, 1981). When segregation occurs, children formulate assumptions that the segregation occurred because the two groups have differences that are important to highlight; thus, biases, particularly intergroup biases, increase. This structure also limits the availability and opportunity for boys and girls to learn to work together (Halpern et al., 2011).

10.3.2.3. The evidence. Most research shows that there is no advantage to single-sex schooling when it comes to overall academic performance. Although you may come across research that seems to support single-sex schooling, flaws in the research have commonly been noted (Leonard, 2006). Findings supporting single-sex schooling tend to disappear when critical confounding factors are controlled for. For example, many students in single-sex schooling tend to be more academically advanced students to start with. Thus, when you simply compare the single sex school (that contains a higher concentration of advanced performing students) to other mixed-sex schools, it seems like single-sex schooling is excelling, and the conclusion is often that this is due to the single-sex context. When researchers control for the more advanced students, there is no statistical difference showing advantages for single-sex schooling (Pahlke, Hyde, & Allison, 2014; Hayes, Phalke, & Bigler, 2011). In the same respect, children that are underperformers will often transfer out of single-sex schooling; thus, continuing to artificially inflate the academic performance scales of single sex schools (Halpern et al., 2011).

The argument that gender stereotypes may be reduced in single-sex schools is not supported. In a Swedish study, it was found that boys were overconfident in math whereas girls were underconfident in math in single-sex schooling; thus, single-sex schooling did not help dispel the stereotype of poor math abilities in girls. Moreover, this was repeated in an El Salvador study which again found the same results (Jakobsson, Levin, Kotasdam, 2013)

Although there does not appear to be a general advantage to single-sex schooling in academic performance, there may be some benefits to single sex schooling. There may be some slight advantages for girls in math though some research shows differing results. For example, Bell (1989) and Spielhofer (2002) found that children in single-sex schools were more likely to choose science than children in coeducational settings. Stables (1990) found that children sought out gender-atypical classes more often in single-sex schooling, and this was particularly true for younger students. However, Francis (2003) found conflicting results revealing that girls showed similar preferences and sought out similar experiences equally in single-sex and coeducational settings (Leonard, 2006).

Overall, there is very little support for single-sex schooling, from an empirical standpoint, and very little is known about the long-term impacts of single-sex schooling and outcomes (Leonard, 2006).

10.3.3 Achievement Motivation

Achievement motivation is the “motivation relevant to performance on tasks in which there are criteria to judge success or failure.” (Wigfield & Cambria, 2010). The motivation to be successful, particularly in academics, has important outcomes. For example, academically motivated youth tend to perform better at school, have increased prosocial behavior, and higher attendance at a school. Females have more intrinsic motivation (e.g., self-motivating) to achieve high in academics, whereas males rely more on external motivation (e.g., praise, external rewards; Vecchione, Alessandri, and Marsicano, 2014). Moreover, an individual’s perceived competence in an area, as well as determination, impact their level of academic motivation, which also impacts their performance in a positive way (Fortier, Valleranda, & Frederic, 1995). Parents who engage in warm, but firm parenting, also foster higher academic motivation.

Attribution styles also impact achievement motivation. Learned helplessness is an attribution style in which failures are attributed to one’s ability and success is attributed to external things such as luck. This attribution style is one in which a person believes they cannot improve on weaknesses, so if a task is difficult, they do not feel hopeless to overcome it. Mastery-oriented attribution style is when an individual explains successes as a result of their ability, as well as explaining failures as a result of controllable factors, such as their effort. They approach challenges as something they have control over, persevering and putting forth effort (Heyman & Dweck, 1998). Master-oriented individuals focus on learning goals whereas learned helplessness individuals focus on performance (Heyman and Dweck, 1998). Children with a learned helplessness attribution style do not end up developing the necessary skills, such as self-regulation, to succeed in high achieving contexts; thus, academic motivation may be lower. If teachers focus more on learning than performance and grades, then they end up fostering more master-oriented students (Anderman et al., 2001). It appears that girls are more likely than boys to attribute failure to ability (Bleeker and Jacobs, 2004).

Boys report more interests and ability in math and science, whereas girls report more ability and interests in language and writing. Moreover, gender differences with motivation show up early and increase as children age. This is especially true with language arts. As children get older, the gender gap in math and science motivation (with boys having more motivation in this area) begins to decrease, whereas as the gender gap in language arts (with girls having more motivation) increases (Meece, Bower Glienke, & Burg, 2006).

Module Recap

In this module, we first focused on understanding the unique experiences of preschoolers and how their development of self-competence and self-esteem occurs, factors that impact their development, and the importance of play in their development. We then moved on to school-aged children and learned about various similarities and differences in their abilities, motivations, and experiences. We also discussed the benefits and drawbacks of single-sex schooling. Finally, we discussed gender differences in academic motivations.

3rd edition